An excerpt from the book “Cabin Lessons: A Nail-by-Nail Tale.”

By Spike Carlsen

Don’t let the nonambulatory state of a cabin mislead you; it’s a living thing. The 100-amp electrical service panel is the brain; the wires are the nerve fibers; the outlets, switches and lights are the nerve endings. The hot and cold water pipes are the veins that nourish. The drain, waste and vent pipes create the intestines that usher the waste away; the cabin is actually superior to us since it expels gas up and through a roof vent, versus humanity’s lower trajectory. The shingles are the hair, the siding and insulation are the skin, the paint is the makeup, the heating system is the lungs, and the rough framework is the skeleton. But you need to start from the ground up. With a cabin, as with any entity, you need to begin with solid feet and legs – the foundation.

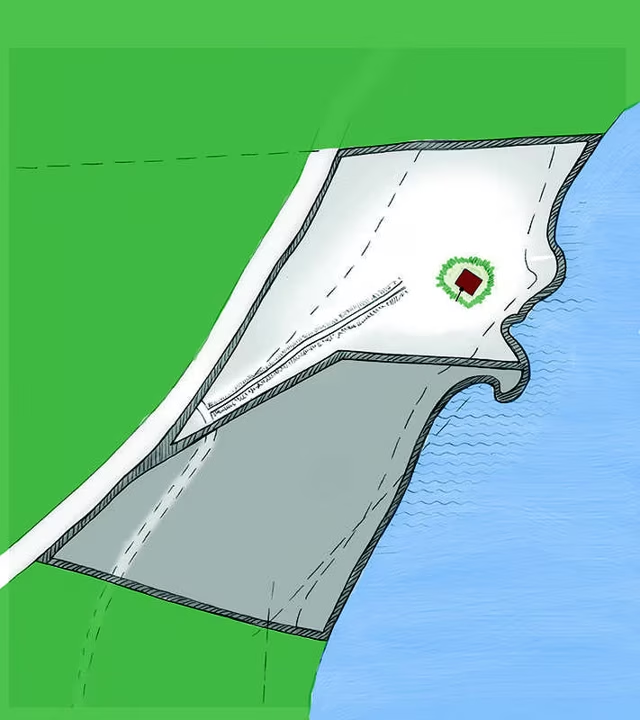

There are two approaches we can take to building on a steep slope. The first is setting the cabin on a full basement; one where the backside would be buried 6 or 7 feet and the front or downhill side exposed. This approach would involve dozing a mammoth wedge of soil out of the earth to create a flat subterranean surface. The upside is we could create both a foundation and usable square footage beneath the cabin. The downside is it would rearrange both our budget and the landscape in a serious way.

The second option is the “stork” approach. The cabin would perch on a rectangular grid of legs or wood posts; taller ones on the downhill side, shorter ones on the uphill. It would be an inexpensive, low-impact way of building. We wouldn’t need a 20-ton bulldozer rearranging the earth, only a 12-pound posthole digger. Posts would allow us to leave the slope of the ground basically unaltered and to tread more gently on the land. And posts would allow us to build quickly and inexpensively.

We go with the stork option, eyes wide open about the drawbacks. With post footings on a steep slope, we realize we will give up the basement to store tools and obnoxious relatives. We’re committing ourselves to hard, tedious handwork – a solid chunk of blood, sweat and tears. To support our 16-by-20-foot cabin we need nine posts – three rows of three – plus two more posts to support the small bump-out on the back. We also need posts to support the front deck, bringing the grand total to 14. We run strings between stakes to indicate the perimeter of the cabin, then pound in stakes to mark where each post will go. Time to dig in.

The hierarchy of soil dig-ability goes as thus:

- Easiest: Sand and dirt. They’re homogeneous, predictable and light.

- Hard: Soil with lots of tree roots, especially those so beefy you can’t chop through them with a shovel. Especially if the roots are so gnarly and ill-tempered you need to be a contortionist with a reciprocating saw to get rid of them.

- Harder: Soils with lots of clay; heavy, dense, sticky clay that clings to your shovel or posthole digger like a campfire marshmallow. You spend as much time scraping gumbo off your shovel as actually digging.

- Hardest: Soils with rocks of all sizes. Small rocks throw your posthole digger off course, medium-size rocks dull it, and large rocks break it.

- Hardly worth attempting: Clayey soil, with roots and rocks; the soil we encounter.

After spending three hours digging the first hole by hand – 16 inches in diameter, 54 inches deep – I calculate I will spend 42 hours on this task alone. This is Cool Hand Luke work. It’s not the way I want to spend an entire week. I need to be smarter than the shovel. A gas-powered auger ain’t gonna cut it. We need a machine. Bradley is booked, so I find the only other excavator in the area who has a Bobcat skid loader with a hole auger attachment. He agrees to meet me at the site at 5 o’clock, after his day job. I recheck and re-stake the location of each hole as I wait. It’s fall, and the temperature drops to 40 as the sun sets. Seven p.m. and still no auger. There’s no cell phone reception, and I figure he’s been waylaid. I’m chilled to the bone and start packing up when I see headlights and a trailer bouncing down the driveway.

“Decided to do ’er tomorrow, eh?” I say, using a tone sarcastic enough to show my displeasure, yet friendly enough to not alienate the only guy within 100 miles who can get this godforsaken job done. “Hell, no. I got headlights!” he says as he fires up the machine. And soon it becomes clear this is not a one-man operation. He sits bobbling on his Bobcat while I, under the glare of headlights, use a shovel and pickaxe to pry and chop the sticky clay off the auger after each plunge. I use a clam digger-type posthole digger to try to lift loose rocks out of the bottoms of the holes when they fall in. Most of the time I’m on my knees. My pants and shirt are soaked, half from sweat and half from the sodden soil flying through the air. We’re working on a slope, so I hand-guide the auger to vertical before each plunge; I’m hoping he’s packed plenty of tourniquets for when this thing rips both my arms off. I spend three hours, frozen, wet and bone weary genuflecting to the auger god.

I’m paying him; isn’t something wrong here? No, if I were on the Bobcat it would be a submarine on the bottom of Superior. Both hands and both feet are required to drive, steer, lift and dump the Bobcat and auger in a coordinated effort. A good Bobcat operator is part excavator, part ballet dancer; Baryshnikov in a hard hat. By the time we’re done, it’s pitch black. I’m soaked, caked in clay, nearly deaf from the noise and sleep deprived – but hey, look at those 14 holes. Beauty is in the eyes of the beholder – especially if the beholder just dodged five days of brutal work.

I ask what I owe him, and he responds, “Well, what’s it worth to you?” And while the correct answer is, “My firstborn son and 10,000 dollars,” we settle on a more reasonable 200 bucks.

The support posts need to sit on concrete pads. Mixing concrete requires water, and there’s plenty of that around – it’s just 200 feet down a 60-degree cliff. We buy three old five-gallon plastic jerry cans at a garage sale, and Kat and I start hauling. To fill the jugs we kneel on jagged rock and force them underwater, using the muscle mechanics you’d use drowning a hippo. We tie ropes from tree to tree, and as we ascend, one-handed, with the 40-pound jugs, we slip, slide, grunt and struggle to keep our footing. This is how people wind up in the “News of the Weird” column. It’s not how two reasonably intelligent people get water from point A to point B. It would be more reasonable to buy 12-ounce bottles of Perrier from the gift shop up the road.

On our third trip up the hill we encounter Dick standing at the top. We’ve known Dick long enough to be able to judge his mood, even before he says something, based on the direction and velocity of his jowls. You do not want to see rapid horizontal movement. But they’re moving vertically, and he’s got a big grin.

We’re wheezing, with high-water pants and burrs stuck to our socks. “Now ain’t that somethin’,” he hoots – the phrase he utters when he doesn’t know what else to say or is reloading for his next quip. “You know we got a garden hose, and you got a truck. I bet we could figure out a better way to do that.” Yah, ain’t that somethin’.

Visitors are surprised to see the cabin perched on nine modest-size posts. Each is made from three “foundation grade” treated 2-by-6s nailed together, making each post 4 ½ by 5 ½ inches in cross section. Not that massive. But wood is incredibly strong in the vertical position, much stronger than it is lying flat or lying on edge. A single vertical 2-by-6, prevented from bending, can support 15 tons before reaching its limits. That means each post can theoretically support 45 tons, and as a group can support more than 400 tons’ worth of cabin.

When we dig the holes, the cabin still looks small on paper. One or two bags of concrete in each hole will support the posts that will support the beams that will support the joists that will support the walls that will support the roof. There can be no weak link in this chain of command.

We get the concrete pads poured and the posts positioned and backfilled. I step back and squint, trying to picture the cabin with all its parts, occupants, furnishings and snowloads. But instead of hearing a deep, booming voice say, “And it was good,” I hear a scrawny little inner voice asking, “Don’t you think nine posts and 15 bags of concrete are a wee bit on the light side?”

Yet, getting the foundation in – whether it consists of nine posts or 50 tons of concrete for a poured basement – is a milestone in cold climates. It means you’re up and out of the frozen soil and can keep building through the rest of the winter. If you’re crazy enough.

“Cabin Lessons” by Spike Carlsen is published by Storey Publishing, storey.com.

Editor’s note:

Spike Carlsen and his wife, Kat, built their own cabin on the rugged north shore of Lake Superior. They named their place “Oma Tupa, Oma Lupa.” Translated from its Finnish roots, it means “One’s cabin, one’s freedom.”

Why build a cabin? Spike explains: “When some couples reach midlife, he buys a red Miata sports coupe and she gets a facelift and a walnut-size cocktail ring. Not us. We decided to buy a nearly inaccessible cliff of eroding clay on Lake Superior and build a cabin together – along with five kids, a handful of friends, and a half-blind, gimpy Pekingese. We decided from the start that the process of building would be just as important as the final cabin. And in the end we wound up with a cabin perched above 3 quadrillion gallons of water and a bucket of memories.”

In the following excerpt, Spike details the process of laying the cabin’s foundation. He begins with this advice: “When you dig a hole, be smarter than the shovel.”

Don’t let the nonambulatory state of a cabin mislead you; it’s a living thing. The 100-amp electrical service panel is the brain; the wires are the nerve fibers; the outlets, switches and lights are the nerve endings. The hot and cold water pipes are the veins that nourish. The drain, waste and vent pipes create the intestines that usher the waste away; the cabin is actually superior to us since it expels gas up and through a roof vent, versus humanity’s lower trajectory. The shingles are the hair, the siding and insulation are the skin, the paint is the makeup, the heating system is the lungs, and the rough framework is the skeleton. But you need to start from the ground up. With a cabin, as with any entity, you need to begin with solid feet and legs – the foundation.

There are two approaches we can take to building on a steep slope. The first is setting the cabin on a full basement; one where the backside would be buried 6 or 7 feet and the front or downhill side exposed. This approach would involve dozing a mammoth wedge of soil out of the earth to create a flat subterranean surface. The upside is we could create both a foundation and usable square footage beneath the cabin. The downside is it would rearrange both our budget and the landscape in a serious way.

The second option is the “stork” approach. The cabin would perch on a rectangular grid of legs or wood posts; taller ones on the downhill side, shorter ones on the uphill. It would be an inexpensive, low-impact way of building. We wouldn’t need a 20-ton bulldozer rearranging the earth, only a 12-pound posthole digger. Posts would allow us to leave the slope of the ground basically unaltered and to tread more gently on the land. And posts would allow us to build quickly and inexpensively.

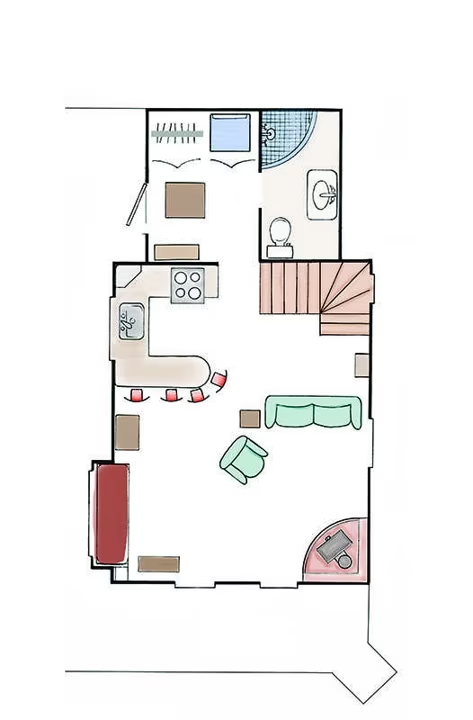

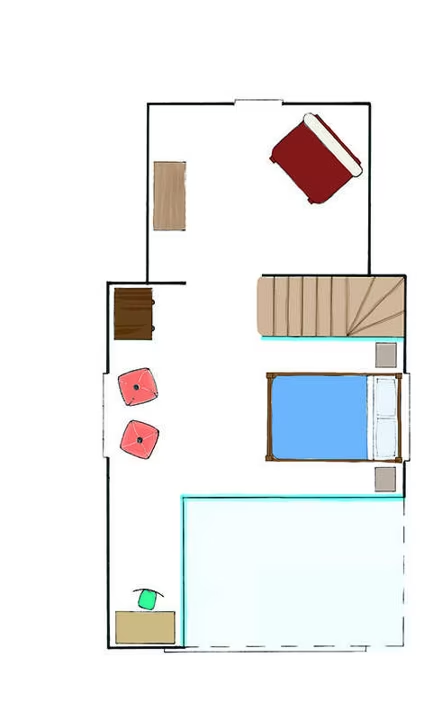

We go with the stork option, eyes wide open about the drawbacks. With post footings on a steep slope, we realize we will give up the basement to store tools and obnoxious relatives. We’re committing ourselves to hard, tedious handwork – a solid chunk of blood, sweat and tears. To support our 16-by-20-foot cabin we need nine posts – three rows of three – plus two more posts to support the small bump-out on the back. We also need posts to support the front deck, bringing the grand total to 14. We run strings between stakes to indicate the perimeter of the cabin, then pound in stakes to mark where each post will go. Time to dig in.

Don’t let the nonambulatory state of a cabin mislead you; it’s a living thing. The 100-amp electrical service panel is the brain; the wires are the nerve fibers; the outlets, switches and lights are the nerve endings. The hot and cold water pipes are the veins that nourish. The drain, waste and vent pipes create the intestines that usher the waste away; the cabin is actually superior to us since it expels gas up and through a roof vent, versus humanity’s lower trajectory. The shingles are the hair, the siding and insulation are the skin, the paint is the makeup, the heating system is the lungs, and the rough framework is the skeleton. But you need to start from the ground up. With a cabin, as with any entity, you need to begin with solid feet and legs – the foundation.

There are two approaches we can take to building on a steep slope. The first is setting the cabin on a full basement; one where the backside would be buried 6 or 7 feet and the front or downhill side exposed. This approach would involve dozing a mammoth wedge of soil out of the earth to create a flat subterranean surface. The upside is we could create both a foundation and usable square footage beneath the cabin. The downside is it would rearrange both our budget and the landscape in a serious way.

The second option is the “stork” approach. The cabin would perch on a rectangular grid of legs or wood posts; taller ones on the downhill side, shorter ones on the uphill. It would be an inexpensive, low-impact way of building. We wouldn’t need a 20-ton bulldozer rearranging the earth, only a 12-pound posthole digger. Posts would allow us to leave the slope of the ground basically unaltered and to tread more gently on the land. And posts would allow us to build quickly and inexpensively.

We go with the stork option, eyes wide open about the drawbacks. With post footings on a steep slope, we realize we will give up the basement to store tools and obnoxious relatives. We’re committing ourselves to hard, tedious handwork – a solid chunk of blood, sweat and tears. To support our 16-by-20-foot cabin we need nine posts – three rows of three – plus two more posts to support the small bump-out on the back. We also need posts to support the front deck, bringing the grand total to 14. We run strings between stakes to indicate the perimeter of the cabin, then pound in stakes to mark where each post will go. Time to dig in.

The hierarchy of soil dig-ability goes as thus:

The hierarchy of soil dig-ability goes as thus:

On our third trip up the hill we encounter Dick standing at the top. We’ve known Dick long enough to be able to judge his mood, even before he says something, based on the direction and velocity of his jowls. You do not want to see rapid horizontal movement. But they’re moving vertically, and he’s got a big grin.

We’re wheezing, with high-water pants and burrs stuck to our socks. “Now ain’t that somethin’,” he hoots – the phrase he utters when he doesn’t know what else to say or is reloading for his next quip. “You know we got a garden hose, and you got a truck. I bet we could figure out a better way to do that.” Yah, ain’t that somethin’.

Visitors are surprised to see the cabin perched on nine modest-size posts. Each is made from three “foundation grade” treated 2-by-6s nailed together, making each post 4 ½ by 5 ½ inches in cross section. Not that massive. But wood is incredibly strong in the vertical position, much stronger than it is lying flat or lying on edge. A single vertical 2-by-6, prevented from bending, can support 15 tons before reaching its limits. That means each post can theoretically support 45 tons, and as a group can support more than 400 tons’ worth of cabin.

When we dig the holes, the cabin still looks small on paper. One or two bags of concrete in each hole will support the posts that will support the beams that will support the joists that will support the walls that will support the roof. There can be no weak link in this chain of command.

On our third trip up the hill we encounter Dick standing at the top. We’ve known Dick long enough to be able to judge his mood, even before he says something, based on the direction and velocity of his jowls. You do not want to see rapid horizontal movement. But they’re moving vertically, and he’s got a big grin.

We’re wheezing, with high-water pants and burrs stuck to our socks. “Now ain’t that somethin’,” he hoots – the phrase he utters when he doesn’t know what else to say or is reloading for his next quip. “You know we got a garden hose, and you got a truck. I bet we could figure out a better way to do that.” Yah, ain’t that somethin’.

Visitors are surprised to see the cabin perched on nine modest-size posts. Each is made from three “foundation grade” treated 2-by-6s nailed together, making each post 4 ½ by 5 ½ inches in cross section. Not that massive. But wood is incredibly strong in the vertical position, much stronger than it is lying flat or lying on edge. A single vertical 2-by-6, prevented from bending, can support 15 tons before reaching its limits. That means each post can theoretically support 45 tons, and as a group can support more than 400 tons’ worth of cabin.

When we dig the holes, the cabin still looks small on paper. One or two bags of concrete in each hole will support the posts that will support the beams that will support the joists that will support the walls that will support the roof. There can be no weak link in this chain of command.

We get the concrete pads poured and the posts positioned and backfilled. I step back and squint, trying to picture the cabin with all its parts, occupants, furnishings and snowloads. But instead of hearing a deep, booming voice say, “And it was good,” I hear a scrawny little inner voice asking, “Don’t you think nine posts and 15 bags of concrete are a wee bit on the light side?”

Yet, getting the foundation in – whether it consists of nine posts or 50 tons of concrete for a poured basement – is a milestone in cold climates. It means you’re up and out of the frozen soil and can keep building through the rest of the winter. If you’re crazy enough.

“Cabin Lessons” by Spike Carlsen is published by Storey Publishing, storey.com.

Editor’s note:

Spike Carlsen and his wife, Kat, built their own cabin on the rugged north shore of Lake Superior. They named their place “Oma Tupa, Oma Lupa.” Translated from its Finnish roots, it means “One’s cabin, one’s freedom.”

Why build a cabin? Spike explains: “When some couples reach midlife, he buys a red Miata sports coupe and she gets a facelift and a walnut-size cocktail ring. Not us. We decided to buy a nearly inaccessible cliff of eroding clay on Lake Superior and build a cabin together – along with five kids, a handful of friends, and a half-blind, gimpy Pekingese. We decided from the start that the process of building would be just as important as the final cabin. And in the end we wound up with a cabin perched above 3 quadrillion gallons of water and a bucket of memories.”

In the following excerpt, Spike details the process of laying the cabin’s foundation. He begins with this advice: “When you dig a hole, be smarter than the shovel.”

We get the concrete pads poured and the posts positioned and backfilled. I step back and squint, trying to picture the cabin with all its parts, occupants, furnishings and snowloads. But instead of hearing a deep, booming voice say, “And it was good,” I hear a scrawny little inner voice asking, “Don’t you think nine posts and 15 bags of concrete are a wee bit on the light side?”

Yet, getting the foundation in – whether it consists of nine posts or 50 tons of concrete for a poured basement – is a milestone in cold climates. It means you’re up and out of the frozen soil and can keep building through the rest of the winter. If you’re crazy enough.

“Cabin Lessons” by Spike Carlsen is published by Storey Publishing, storey.com.

Editor’s note:

Spike Carlsen and his wife, Kat, built their own cabin on the rugged north shore of Lake Superior. They named their place “Oma Tupa, Oma Lupa.” Translated from its Finnish roots, it means “One’s cabin, one’s freedom.”

Why build a cabin? Spike explains: “When some couples reach midlife, he buys a red Miata sports coupe and she gets a facelift and a walnut-size cocktail ring. Not us. We decided to buy a nearly inaccessible cliff of eroding clay on Lake Superior and build a cabin together – along with five kids, a handful of friends, and a half-blind, gimpy Pekingese. We decided from the start that the process of building would be just as important as the final cabin. And in the end we wound up with a cabin perched above 3 quadrillion gallons of water and a bucket of memories.”

In the following excerpt, Spike details the process of laying the cabin’s foundation. He begins with this advice: “When you dig a hole, be smarter than the shovel.”