How to design a cabin that fits your needs & lifestyle.

By Dale Mulfinger My favorite architectural task is standing on unbuilt property and imagining my clients' floor plan for their dream cabin. The morning sun is streaming into the kitchen here, the view from the living room area to the gurgling stream is over there, the entry from the future driveway is back by the birch tree, and if we prop a

ladder up against the poplar tree we’ll see the sunset view from their bedroom. If you have a vivid imagination, you, too, can create floor plans. Just don’t waste your precious time until you have a specific property in mind.

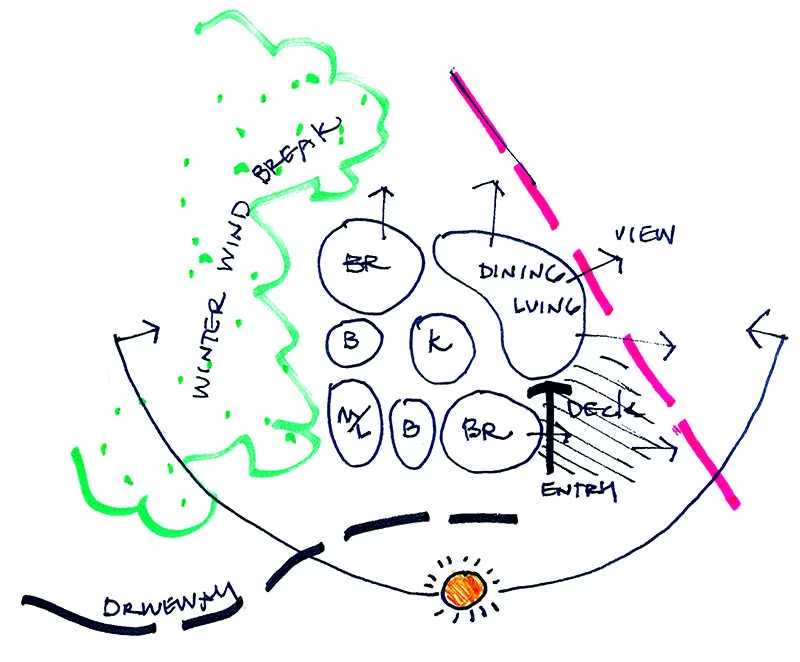

Diagram your cabin lifestyle

A good cabin plan is best started with a diagram where relationships of functional elements of cabin living can be arranged in accord with site opportunities of access and view. Separate diagrams for each level are necessary with the stair being the connecter between levels. One easy way to approach this task is to create “bubble diagrams” with a circle for each of the main activities of your home, such as sleeping, eating and seating. The bubbles can be arranged and re-arranged easily as you evaluate which areas should be adjacent to each other.

Explore roof forms

Once your diagrams feel comfortable, your next step is to contemplate roof forms. This may surprise you, but good plans can be found under a good roof but the reverse is not necessarily true. Gable roofs usually yield rectangular plans, hip roofs are for square plans and at roofs give the greatest freedom for plan shapes. To explore roof forms, try folding paper into the different shapes. This will help you understand the opportunities and limitations each roof form offers.

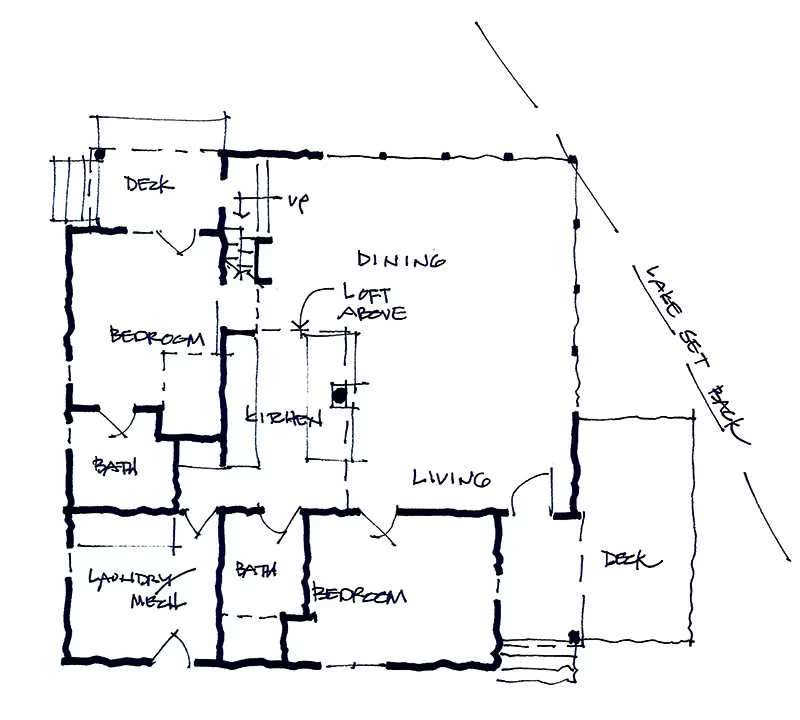

Plot it on paper

A floor plan then can be created in a marriage of diagram and shape. Graph paper will give scale to this enterprise but be prepared for multiple iterations. A good plan takes time to develop, and it’s best to sleep on it a few nights and consult with other likely users. The graph paper will make it easy to eventually add cutouts of furniture you desire in your plan. Cutouts are preferable to drawing the furniture, as you can move them around until you achieve a comfort with them and then tape them down.

Plan smart

Well-designed cabin plans that make good use of space might include some of the following features:

Corridor-free: A plan without corridors is best for utilizing the social spaces of living/dining/kitchen for circulation. Even in the bedroom wing or second floor, a loft or central library space is better than a corridor.

Stair at the entry: The stair serves best if located near the center of the plan and convenient to the entry for luggage access to bedrooms up or down. A switchback or right-turn stair might help with planning the stair ow with each level.

Kitchen at the heart: Food prep and cleanup are a big part of the social life of a cabin, and thus kitchens need to be central to eating areas inside and outside the cabin.

L-shaped kitchens with an island: Optimal for the cook, this configuration can be located to keep general circulation away from boiling pots.

Bedrooms at the corners: Closed-off sleeping spaces are best kept to the periphery of the plan for solitude and privacy. Additional sleeping can be offered in a variety of locations, such as lofts, window seats, garrets, porches and even under the stairs.

Clustered plumbing: Bathrooms, kitchen, laundry and water heater are best clustered in close proximity to reduce plumbing costs and make it easy to drain down the system. In cold climates, it’s best to keep plumbing off perimeter walls.

View people first: Views to lakes, rivers, mountains and meadows are important, but never as precious as human bonding – the soul of what a cabin is all about. You’ll spend more time looking at your friends and family than staring at the mountain peak. With your graph paper plans and folded roof model in hand, you’re ready to approach your architect or builder. Either will be able to evaluate the workability of your concept and its viability within your budget.

The Wright Roof

Roof forms can be a greater challenge than floor plans, and even great architects struggled to form great solutions. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright began his career designing steep-roof multistory houses, as shown in his studio and home in Oak Park, Ill., built in 1890. His designs gradually became horizontal and employed hip roofs, or an occasional shed roof, such as in the Wiley House in Minneapolis in 1934. He ultimately needed greater plan freedom and moved to at roofs in the Jacobs House in 1937 in Madison, the rst of many Usonian houses. Fortunately, cabins are usually smaller and less complex than houses, so if you keep the exterior shape of the oor plan simple, you’ll spare yourself Frank Lloyd Wright’s struggles.

Cabinologist Dale Mulfinger regularly designs cabins with Minnesota-based SALA Architects, teaches cabin classes and gives talks on cabin design across North America. He has authored five cabin-centric books.